Taravat Talepasand: Experiencing your work in person was like “You had me at Hello.” Your conceptual playfulness and masterful painting and ceramics practice is stupendous. Flawless. Tender and funny as hell. Would you describe yourself in this way or is there a separation between you and your work—who you are and your work?

Erica Eyres: No, I don’t think so. I’m always glad when people find it funny, first of all, but also this idea of tenderness is important to me as well that I never wanted to feel like I’m making fun of the people or the figures that are in the things. Even with the objects, I’m really happy if people relate to them in a personal way. Sometimes they are quite personal or there sort of drawn on things I remember having or having some relationship to. Yeah, I am always hoping that other people will relate to them with their own experiences. Say with the paintings, the last time people were like “oh, this looks like someone I know.” I feel like that too, even though I’m usually working from an image, but then it changes at some point and then I keep thinking that it looks like someone other than the image—so it does kind of take on its own life. I don’t think that there's a separation between me and my work.

I had to do a talk for work yesterday to students that were doing this modular on portraiture and they’ve got this concept that they're working from that is the self and the other where they have to do two different projects. I was saying that I don’t know how you separate those things out because you find the self through the other, if that makes sense? I’m not always interested in working directly from my own narrative, but there’s something about finding something and just being attracted to it and not really knowing why and then that there’s something about yourself that is revealed through that process.

TT: It’s like you’re creating a spirit or a type of consciousness with the work. You’re so dedicated both to the research and finding it naturally, like an easter egg hunt or something you deep dive to find. There’s something inherently calling you and that you’re connected with in that moment whether you know it or not. But when you plan on dedicating a painting or a sculpture that are both very laborious ways of working—You’re going to find a way to personalize it or expand on the narratives whether it’s familial or a social commentary on communities or specific niche of people or things—all which are readily available to find and experience. I love that you do that.

EE: Oh, thank you, yeah. I too like that you don’t always know that it’s happening because you're just working and you have this aim that it’s going to look like this, but that there’s something else that’s going on that maybe you’re not aware of that is happening. I guess that it just comes through in dedicating to that labor that you’re working with.

TT: Absolutely—working through the work!

TT: The works in this exhibition present figurative narratives around human pleasures, fallacies, discomfort, vulnerability, play—that’s humorous, discomforting, and at times unsettling. Inviting the viewer to consider and reconsider the confrontational portraits of mostly nude solitary female figures, except for the painting Dora…

EE: Oh, yeah, cause she’s not nude…

TT: Let’s talk about your paintings. I made a little presentation that I thought would be fun. I’ve put together some comps of Sargent, Currin, and Yuskavage that to me are in conversation with these works and that we can talk about together.

EE: It’s so funny because when I was first doing those paintings I had this conversation with my friend on Zoom, she lives in Connecticut, and we were talking about painting and how much she loved John Singer Sargent and we were looking at different examples of his work and especially the treatment of the clothes for some reason.

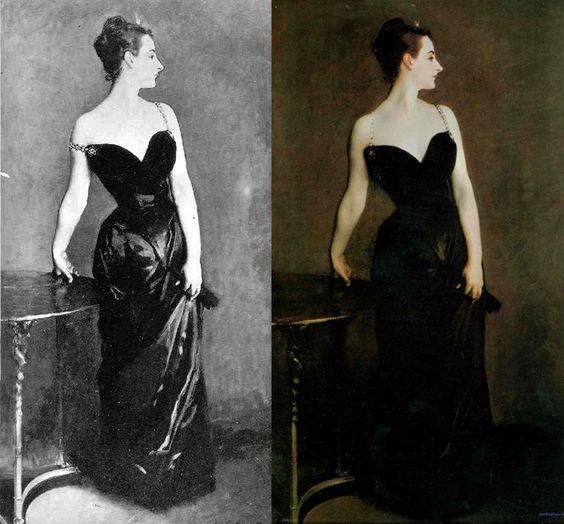

TT: Yes! When I was studying at RISD, this painting was at the RISD museum. So I got to visit and study it every single day—getting right up close to it, staring and in awe of the pleasures he had with painting and learning everything about Sargent, specifically this portrait of Madame X. What I think is so interesting about this painting is that the painting to the far right is the original painting, what we can view it as today. But the black and white image to the left is what he had actually first painted with one of her straps hanging down which created a scandal in the art scene.

Artist Profile: Erica Eyres

interviewed by Taravat Talepasand

Erica Eyres, Dora, 2020 Oil on panel, 12 x 9 inches

featured in Hog Gob at Helen's Costume.

Erica Eyres photographed by Karen Asher

John Singer Sargent, Madame X, original and after the controversy

Erica Eyres, Chicken Burger, 2022, glazed stoneware, and Maggie (with Abstract Painting), 2020. Oil on panel, 12 x 9 inches.

EE: Really? Do you know why she was called Madame X?

TT: (Read from Wikipedia) Madame X or Portrait of Madame X is a portrait painting of a young socialite, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, wife of the French banker Gautreau. Madame X was painted not as a commission, but at the request of Sargent. It is a study in opposition. Sargent shows a woman posing in a black satin dress with jeweled straps, a dress that reveals and hides at the same time. The portrait is characterized by the pale flesh tone of the subject contrasted against the dark colored dress and background.

The scandal resulting from the painting's controversial reception at the Paris Salon of 1884 amounted to a temporary set-back to Sargent while in France, though it may have helped him later establish a successful career in Britain and America.

Madame X was an American expatriate who married a French banker, and became notorious in Parisian high society for her beauty and rumored infidelities. She wore lavender powder and prided herself on her appearance. She was referred to as a "professional beauty" –an English-language term for a woman who uses personal skills to advance herself socially. Her unconventional beauty made her an object of fascination for artists; the American painter Edward Simmons claimed that he "could not stop stalking her as one does a deer." Sargent was also impressed, and anticipated that a portrait of Gautreau would garner much attention at the upcoming Paris Salon, and increase interest in portrait commissions. He wrote to a friend:

"I have a great desire to paint her portrait and have reason to think she would allow it and is waiting for someone to propose this homage to her beauty. If you are 'bien avec elle' and will see her in Paris, you might tell her I am a man of prodigious talent."

Although she had refused numerous similar requests from artists, Gautreau accepted Sargent's offer in February 1883. Sargent was an expatriate like Gautreau, and their collaboration has been interpreted as motivated by a shared desire to attain high status in French society.

EE: Interesting…It sort of was a profession at one point, I guess it sort of still is. This kind of, I don’t even know what you would call it, the way to gain power through men.

TT: Yes, this idea and comparison came rushing to my mind when I saw the painting of Dora.

EE: Very interesting, I was listening to someone talk about Camilla Parker Bowles who’s married to Charles and how that was in a strange way her profession—Trained to go after high society men and that’s how you attain status. When you read it you kind of think about a different time when that was more widely accepted, but it still happens of course. It’s always going to be a profession for different social classes on economic levels. But yeah, it’s so interesting…

TT: It seems like that in this series it’s coming from a very different position, even though I think about Madame X and women in society whether it be positions of power, pleasure, or play, there definitely seems to be a little bit of both that is happening in these portraits. For example, I made this connection between your painting Maggie with John Currin. This is a quote from GQ Magazine that kind of makes me uncomfortable “A man clutches a beautifully rendered penis in the presence of a woman’s bazongas. Office Workers, 2010. Oil on canvas."

EE: (Laughs) That’s so funny, like her boobs are not, they're such an odd shape, I dunno, they’re…

TT: …unnatural and phallic in a way themselves.

EE: Yeah, like I don’t know if they’re an eggplant or something, it’s such a weird sausage shape. Again, I love John Currin, and was just thinking recently of his exhibition in London and I love going and looking at paintings in person because that’s how I think anyone learns to paint, by looking at painting or that’s at least half of it you know. But also I feel so different than that too. There are many things that I love and admire about his paintings. This in particular is so different to me than anything that I want to do. I think that I’m always looking for images at least within this series of women that are looking right at the camera. I have this criteria in my mind when I’m looking for women who are looking at the camera, and there's certain ones that work and certain ones that don’t. There's a different power play happening in this Currin painting I think.

TT: Yes, there’s other Currin paintings that focus more closely on women caught in humorous discomforting moments. A better comparison that I found with your portrait paintings of women is that of Lisa Yuskavage’s Créme Pie.

EE: I have two anecdotes about these two artists, but I did see Currin once in New York. I was on holiday and while visiting a gallery he walked in with his wife. I was looking at her. You can tell that they were of some importance by the way people were greeting them. I kept looking at her thinking—who is she, she’s so familiar—and then I realized who it was somehow. I recognized her from what I think were his paintings and she's in so many of them and she has such a distinct look about her. His paintings are exaggerated, but you can still see where it comes from strangely.

TT: I love that you have that personal story and moment running into or past Currin and his wife—that’s fun to share. But here with your portraits of these women that you are finding online that you don’t know personally, but as you said that you’re looking for that gaze, that connection of looking outwardly in a personal provocation in their own private spaces. Tell me more about finding these images and deciding on which woman you feel like painting and why?

EE: It’s hard to describe because it can be intuitive at times. I order these magazines—I have this niché of magazines that I order based on titles, but I don’t know what's going to be in them because I buy them on Ebay. Sometimes the pictures on Ebay are half covered by a paper bag or something and sometimes are partially covered up, so it’s a surprise. I’m so excited when they arrive and can’t wait to look through them. I go through them really fast and sometimes there will be one where I immediately know, yes, that one definitely. Sometimes I’ll take pictures of them and zoom in, more so than the ones in the show, as I was more fixated on the faces at some point. I’d go through the pictures thinking about which one’s would look better. Some of it’s difficult to describe. It doesn't necessarily have a formula, you just know that there’s something in it. a kind of awkwardness in the pose. I think that in those specific magazines the women are fairly professional, sort of like a scene in different publications, a scene of women revolving around each other. I prefer if they are looking at the viewer because for me that is part of the discomfort as they are addressing you.

When I had a show a while ago and had them for the first time up on this one wall, four of them together, I felt like whoa, what do they want? As if they were asking me for something and I didn’t know what it was. When I first started painting these portraits I was thinking about clothing and really interested in the colors and what they were wearing, different types of clothing, and fabric. For a long time I was interested in black and white drawings so I think painting opened up color in a way that I wasn't able to do, so I would get really excited by a certain color. Like the painting of Maggie on the table, I really liked that there’s this abstract painting behind her on the walls. Even the tiles and the whole scene and patterned tablecloths and that painting was more figurative but I changed it to simplify it. So, sometimes I’ll change the background slightly if I feel like there’s too much information. It’s a strange kind of kinship that happens with the figure as I’m doing it that is difficult to describe. I think that part of it is that if I didn’t try I feel like they would all end up looking like me somehow in the face. So I’m somehow making an effort to try and capture something in the face specifically, like an expression or their particular features. They always end up looking different and don’t look exactly the same to me. I do feel like there is something to do with empathy in that trying to inhabit them in some strange way.

TT: Well deciding to make a painting of them is in a way memorializing them. It’s definitely an ode to these women who are putting themselves out there in an uncomfortable and vulnerable way. I love that you as a female artist take agency to do that and give that power back to the women within the painting practice.

EE: Oh, well that’s good (laughs). I think it would be so different if a man were doing this.

TT: I think that we are in a place right now, no, I know that we are in a place right now in the art world where we are more aware of and questioning artists' intentionalities behind their work. For example, I don’t see a lot Will Cotton paintings anymore painting women sexualized in candy land settings and attire—nah, that’s enough (laughs)

EE: (Laughs) Yeah, nobody wants to see that (laughs) They're not canceled, you just don’t see it around anymore.

TT: That’s really great that there’s this sense of awareness and interconnectedness throughout artists from different cultures, genders, sexuality, ethnicity, etcetera. Where artists are ethically being challenged and taken into consideration—a much safer place to create, play, and experience.

You have an amazing painting and ceramics practice. As you are also known for what has been described as “obliquely disturbing films and drawings, simultaneously endearing and grotesque”. Here the inclusion of your ceramics are almost equally odd. Positioning hyperrealism with a faux twist on capitalism, food, accumulation, as these are dynamics found in both public and private spaces. I found similarities between your ceramic and that of John De Fazio, a lil’ bit of Chloe Wise, and more adjacent with Genesis Belanger. How do you visualize your paintings and ceramics together in an exhibition?

EE: I actually didn’t know about John De Fazio, but I do know Genesis Belanger and love her work. I have this kinship to it, but it’s different from what I do as well, but we are attracted to similar objects. Like I was just thinking today of making a book of matches, but it’s also different, a kind of dreamscape of her works. It's hard to describe what it is but we are both interested in the uncanny quality of objects.

I guess I should answer the question behind the painting and ceramics first. I feel like I’m trying to create narratives by trying to resist it in some ways. Sometimes I’ll feel like I have to take this out because it’s too pointed, that the narrative is becoming too much. Generally, if i’m having a show i’ll have a long list of stuff that has been edited down already and I’ll bring it into the space and start playing around with it and seeing what happens. But also, I take a lot out and remove things. I had a show where I had the paintings and sculptures connected with a deflated doll, not a sex doll, I think that they are more for stag parties but it made a bridge between the paintings and sculptures and then there was the food. I think for me that on a personal level they do connect. The food references a childhood that I remember having around, like McDonalds. The paintings sometimes I feel like they stem from childhood memories that I remember seeing for the first time. Like finding my dad's magazines or I have this weird memory of my mom dating a guy and just finding these weird Penthouse magazines laying around. He had these wallpaper drawings of these nude women and it really lodged in my brain for some reason and kind of like horrified but also thinking “what is that''? There’s always a personal connection there. It’s tricky because it depends on the show itself and where it is and if there are other artists in it. What type of space is it? What's the overarching narrative of the show? They all connect but in a very careful way I suppose.

Erica Eyres, Dog mask, 2020 glazed stoneware

Erica Eyres, Chrissy 2020, oil on linen, 27.5 x 27.5 inches

Erica Eyres, Grace (with latex catsuits), 2020, oil on panel, 12 x 9 inches

Featured in Hob Gob

TT: Well, that makes sense because painting has a history and especially that of figurative works of giving life to life. Your sculptures are props for the body or things that the body consumes—there’s definitely a direct relationship to the body but it’s an object being objectified. For example, you have the chicken burger on a shelf near Maggie. I can imagine that this beige burger would be something that Maggie would eat with her diner style hairdo and tablecloth. These are just connections that are based on my own associations to the body and culture, but also another layer of surprise seeing your work in person. I didn’t expect that the sculptures would be made, but once I did, as an artist, I had even more respect for you because you know how to paint really well and you know how to create ceramics with superbly painted glazes. I know first hand that that is really hard to do.I thought, WOW, this woman can create magic and meaning out of anything and everything that I can connect with as a woman and with my childhood.

EE: So good to hear!

TT: How do you feel about your work traveling across oceans and being seen and experienced here in Portland as you are located in Glasgow, Scotland?

EE: I’m always excited that my work goes somewhere. I do get attached to the works but if they are able to go and have a life somewhere else that makes me really happy. I wished that I had gone to the opening as I loved seeing the documentation of it. That it was in a sort of domestic space that was attached to Steve’s house—I loved how he put everything together. Something weird about the shoes that are on the wall is that they have a weird glow about them that really relates to that painting of Dora—like wow, that looks so strange that I wished I could've seen it in person. I’m always interested in my work being seen in the North American area as I’m from Canada and I wonder if there are different references that people pick up on in my work.

TT: What is the one thing that you would want a viewer to take away from seeing your work?

EE: I was really excited about all the stuff that you were saying at the beginning—oh wow, this is what I really want, a series of complex emotions that it’s not really just one thing. It’s funny and sad, tender and that people are able to bring their own story or narrative to it. That’s what I want. I don’t like it when work has one reading. Not so much now, but maybe like five or ten years again especially in Glasgow everything had this back story to it or found narrative. There was this artist that was very big for awhile, well, he still is—Simon Starling that involved all this complex narratives and stories. It’s not that I don’t like that work, it was just research and anthropologically heavily driven and that you had to have this story to access this work which is oftentimes very minimal in terms of its presentation. It’s just not for me. I really like it when it can allow for more than one reading. I was watching the Netflix Warhol documentary and I found it very interesting that all these people had these totally different takes on the works and how he doesn't really offer much. It seemed quite strategic that people had to find their own meaning in the works. I’m not closed off or anything, but that I’m happy if people can see humor in it but also other emotions that are maybe conflicting with that like tenderness and sadness that for me are just what human experience is.

TT: No doubt does your work feel like an invitation for anybody and anybody to experience. The sentiment of the female figure and the power of the body and sexuality by making a comparison to the things we consume or are consumed by. Whether they be found in plain sight in your home or tucked away under your bed, for me it really centers around the associations or dissociations between the body and the mind. This can be a difficult challenge in an art practice, but you manage to do it in the most beautiful way and I thank you for that.

What are you working on next?

EE: I’m still working on the painting and working on a different series for a summer show in Winnipeg Canada and I really wanted to do more personal but still removed so I started working on these instructional book that you give children in the 80’s & 90’s for divorce or adoption or bullying and they are modeled by child actors. Again, there’s this choosing on what’s more emotional and zooming closer and closer to the image. Working on more ceramics that are based on books—partly my idea but taken from all these copies of Lolita and I have this fascination with the cover. I think that Richard Prince did a similar thing where had a show in the National Library ten years ago where he had all these copies of Lolita and I think that stuck in my mind and how this invisible figure is represented in various ages. Playing on that relationship of books that I like or have an antagonist relationship with.

TT: Anything you create feels so authentic and with the right intentionality and that’s what I’m personally looking for in the art world—Big Bow to you Erica.

Taravat Talepasand is a Portland OR based interdisciplinary artist.

Erica Eyres, Child mugs (Minnie, Pluto), 2022 glazed stoneware

Erica Eyres, Red Glove, 2022 glazed stoneware

Erica Eyres, A Pool of Blood (clip), 2017, HD video, 22 min

Erica Eyres, ,1973 Copy of Lolita, 2022, glazed stoneware